JOHN ('JACK') KNIFTON 1855-1896

Pugilist, Court Bailiff, and Vestryman

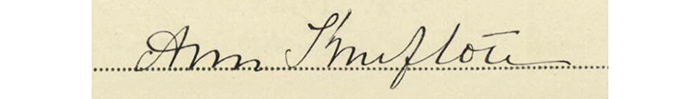

ANN ELLIS 1853-1933

By Kevin Knifton 26th August 2022

John Knifton was born on 22nd January 1855, the first son of John Knifton, a smith and cowkeeper, and his second wife Maria (née Johnston). Known as Jack, some reports state that, like his mother, he was born in Scotland. This likely came from Jack himself who, during an interview, said "I was born at St. Cyrus, near Montrose, Scotland." However, all but one census return records that he was born in Shoreditch, London. This is also where his birth was registered, so it is likely that Jack was deliberately misstating where he was born.

Jack was the first of 13 children of John and Maria, although Jack had an older sister Ann, the only child of John and his first wife, Elizabeth.

Jack's brother David was born a year later, and in their early years were brought up together by their grandmother in Scotland.

By June 1861, Jack was back in London, living with his parents at 30 Bartholomew Place, Hackney, together with his brothers David, Joseph, and William.

Jack said that he "listed when I was 14 years and a half old." This would have been in July 1869. Jack joined the 2nd Regiment of Life Guards, a cavalry regiment in the British Army. Recorded as being a 'trooper' on the 1871 census, he was at the Cavalry Barracks on Spital Road, New Windsor, in Berkshire. He gave his age as 19, although he was actually 16, and his place of birth as Montrose in Forfar, Scotland. This is the only document which claims Jack was born in Scotland, and since he overstated his age, perhaps in order to qualify for enlistment, he may also have misstated his place of birth to disguise his true identity.

Jack said that "I was always an athlete" and while in the army "I was champion runner and jumper of the 2nd Life Guards, and at Bourley Bottom, Aldershot, beat the whole Brigade of Guards."

Jack tells us that he was only in the army for "about three years", which suggests that he left in 1872. He then started working as a 'contractor'.

On 13th April 1875, Jack married Ann Ellis in Islington, London. Ann was born in 1853 in the St Clement Danes parish of London. She was the daughter of John Ellis, a cow keeper who originated from Aberystwyth, Wales, and his wife Ann. The Ellis family kept dairy cows in London.

After their marriage, Jack and Ann lived at 17 Hertford Road, Kingsland, in Hackney.

Jack and Ann's first child was named John. He was born in Hackney in January 1876 but died aged 6 months. Jack and Ann buried John in Abney Park Cemetery on 6th July 1876.

Their second child was born in February 1877 and named Frederick David Knifton. As a boy, Frederick joined Jack on several of his boxing expeditions.

Jack and Ann's third child was named Francis. He was born in November 1877 but survived for only a week. Francis was also buried in Abney Park Cemetery.

Between 1879 and 1881, Jack spent some time in Canada. During an interview he said "I have repeatedly been complimented for bravery in other directions. When in Toronto, at the risk of my life I rushed after a runaway horse and buggy, and catching hold of the reins managed to throw the horse down. I was there known as Knifton, the English cattle dealer." Jack also brought bison back from Canada: "It may be interesting to you to know that the bison buffalo now in the Zoological Gardens was captured by me under extreme difficulties and danger, and conveyed to England, where I sold it to Mr. Bartlett." Abraham Dee Bartlett was a taxidermist, an expert on captive animals, and a superintendent of the London Zoo.

Also between 1877 and 1881, Jack and Ann started keeping cows. For a short time the family lived at 3 Meadow Row, Newington Causeway, but then moved to 109 Britannia Street in Shoreditch. Jack's brother David and his wife Alice were also living with them around this time, helping with the cows.

Born in May 1881, Jack and Ann named their fourth child Arthur James Richard Knifton. Arthur would later go by the name of John Knifton.

Jack's father John died in 1879 and Jack took over the keeping of his cows on Hertford Road. Jack and David were also keeping cows at 3 Fanshaw Street in Hoxton.

|

The Post Office Directory, London, 1882

In 1883, Jack's cow keeping business was in financial difficulty. A meeting of his creditors was called. This may have resulted in the business being transferred into Ann's name.

|

Benjamin Clark George Knifton, Jack and Ann's fifth child, was born towards the end of 1883. He was followed by their first daughter, Ann Maria Knifton, in January 1884, although she died at the age of 1 year. A second daughter, Edith Ethel Knifton, was born in April 1885, but she died at the age of 6 in 1891.

By a personal friend of his for many years, Jack was described as 'a good husband and an indulgent father'. We know that he enjoyed ratting, and kept dogs and ferrets for this 'sport', and stood at just over 6 feet tall. Although working as a dairyman, by this time Jack had become renown as a boxer.

The Eighty-One Tonner

When asked what first induced him to follow boxing, Jack said that in 1876 "I was a constant visitor at Ted Napper's, and I thought I should like to try my hand at the game." Ted Napper kept the Five Ink Horns pub at 31 Nichol Street, Shoreditch (now demolished), and this is where Jack gained his schooling. An article in 1934 claimed that 'the big fellow learned to spar pretty well after heaps of tuition from his lightweight school-master...Napper thought highly of his pupil, and was often heard declare that "he (Knifton) hits me bally hard, guv'nor; and I don't suppose the other blokes'll like it any more than I do"'. Jack's younger brother David was also a pupil of Ted Napper.

|

An early likeness of Jack Knifton

Jack was originally known as 'Napper's 81-Tonner', but became more widely known simply as 'the 81-tonner'. An article from January 1885 suggested that this was 'a playful cognomen no doubt derived from this gentlemanís second name', while others have suggested it was in recognition of his strong punch. In 1874, the Royal Navy introduced to its fleet the largest gun it had engineered. Installed on HMS Inflexible, the gun was 27 feet long and weighed 81 tons. I believe this is what Jack was named after.

Jack said that his first fight was in May 1877 "at Sadler's Welis Theatre, Charley Frank's open competition. I won, after beating Jem Madden, Tom Tully, and Walter Watson." Jack beat Jem Madden after two rounds, and Walter Watson after one round, both with knock-outs. These fights were with gloves. There is a record of an earlier fight between Jack and Walter Watson in August 1876, which Jack won after four rounds, and may have been without gloves.

|

Another early likeness of Jack Knifton

Jack's next fight was with Tom Scrutton at Cambridge Hall, Newman Street, London, on 4th September 1877. The contest was for the Championship Heavyweight Cup, and prize money of £25. Jack's trainer was Jemmy Howes, who is said to have brought Jack 'to the mark in the pink of condition'. A report at the time described Jack as 'a splendid specimen of an athlete'. Jack was 21 years old, 6ft. 1¾in. tall, and weighed 14st. 2lb.; Scrutton was ten years older, was 5ft. 8½in. in height, and weighed 15 stone, with 'a deal of flesh being carried below the belt'.

Before the fight, there were several exhibitions of sparring. At 10.45 p.m., Jack and Tom entered the ring, which was on a raised platform in the centre of the hall. 'Several rounds were fought of a wild rough and tumble character, but as they had "mittens" on little physical damage was done. During the contest the excitement had been intense, most of those present shouting out advice, not unmingled with curses, to the struggling men.' The fight had attracted a 'with well-nigh as motley and ruffianly a crowd as could be brought together'.

In the early rounds, Jack and Tom were reported to be 'hugging each other as closely as possible, and reeling all over the ropes'. Just before the end of the third round, 'the gas [was] partially extinguished by the proprietor of the hall, who, seeing the turn affairs were taking, wished to put an end to the proceedings.' There then followed a 'noisy altercation between the seconds and others connected with the fight' after which 'another round was fought in partial darkness, amidst an indescribable scene of confusion...the gas was continually being turned off and on...the fighting and mauling continued till eight rounds had been gone through, when the hall was put in total darkness.'

After several minutes, the referee started the fight again, but Jack and Tom 'were terribly exhausted'. The lights went out again, and it was reported that 'the referee left, refusing to give a decision, and so the result remains in abeyance'. Another report said that two rounds were fought in the dark, and that the referee then stopped the contest due to crowd disturbance, with fighting in the crowd.

In recalling this fight, Jack explained that he "beat Scrutton in a glove fight, at Newman Street, Oxford Street. There was a disturbance over this, and the glim was doused. The referee ordered us to meet the next day at two oíclock, and Scrutton not appearing, I was awarded the stakes."

Almost sixty years later, this 'extraordinary show' was recalled in an article in 1934 which noted that after winning this fight, Jack 'dropped his amateurship and blossomed into a pro. In that capacity he visited America, though he did no fighting there'.

|

Jack's father John is reported to have attended his fight with Tom Scrutton 'and whenever Knifton scored Jack would turn to the old man, who was one of the spectators, and exclaim "How is that, father?"'

Following his win against Scrutton, Jack said that "I challenged anybody to fight in the old style, but could not get accommodated until Massey obliged me." The old style was bare-knuckle. Since no one took up Jack's challenge, his next fights were with gloves.

In October 1877, 'Jack was challenged by Tom Allen for the Heavyweight Championship of Britain. Jack was unable to find the backing for his fight with the famous Allen, former American Heavyweight champion, and forfeited. He was an equal opponent for the old Tom.'

In 1877, Jack and his brother David began appearing in exhibition shows. Exhibition fights were popular at fairs and on the stage. Their purpose was to demonstrate the boxer's skills, and no winner would be declared from these bouts.

On New Years Eve 1877, a 'boxing entertainment' was held at Ted Napper's saloon. Jack appeared with 'Mars', a Grenadier Guard, while David, described as 'the 81-Tonnerís little brother, who only scales 12st when fit', sparred with Napper.

|

Jack and David also appeared in a boxing show at the Cambrian Palace, Castle Street, Leicester Square, in February 1878. Again Jack sparred with 'Mars', and David sparred with Napper. In an early round Mars 'got a stinger that shook him like a thunderbolt would from his patron saint' and fell to the ground. In 'the third and fourth rounds Knifton was sportive again. Rib music was long and loud; Knifton became an open target, at small range, and the soldier got at his bullseye regularly in fine style. Knifton, who is a giantly style of "pug" senior, forced his fighting, manifestly having had his rations. This divertissement of "box" terminated after a hard-fought rally, the son of Mars coming off with flying colours.'

In June 1878, Jack and David sparred together in a boxing shown before 15,000 spectators at the Alexandra Palace. Later in the evening, Jack appeared in a 'fine glove encounter' with Bat Mullins; 'Mullins, despite a disparity of nearly five stone in weight and eight inches in height, acquitting himself magnificently, and drawing blood in a copious stream from the big unís nose, although neither boxer lost his temper.'

No exhibitions or fights involving Jack were recorded from 1879 to 1881. I believe Jack was in Canada at this time.

In December 1882, Jack fought Woolf Bendoff and Coddy Middings in London. These bouts were part of a Billy Madden Heavyweight Championship and were with gloves. Both fights went three rounds, with Jack beating Bendoff on points, but losing against Middings, also on points.

His next 'glove contest' was on 3rd January 1883 with Roger Wallis at 'a well-known rendezvous near the Strands'. Jack was 6ft. 1in. tall and weighed 17st. 4lb., while Roger stood at 6ft. 2in. and weighed 14st. The fight was mainly for a visiting American promotor to test the ability of Roger Wallis. The bout was for three rounds, which ended in a draw. Jack was described as being 'very much out of condition': 18 months later, he was down to 14 stone (89 kg).

Jack continued with exhibition fights, appearing in London in November 1883 with Charlie Mitchel.

The fight with Massey came about on 10th July 1884. This was for the Heavyweight Championship of England, and bare knuckle. Jack said "The fight, as you know, took place at Pulborough, and I won easily, after fighting 39 rounds (41 min.). This was my first and last fight in the old style, and I may mention, by-the-bye, that my seconds, Jem Smith (with whom I am now matched) and Coddy Middings, were then just as inexperienced, never having previously seen a fight in the old style." At the end of the 38th round, Massey gave in. Jack had a weight advantage at 14st. 7lb. compared to Massey at 11st. 8lb.

|

On 6th October 1884, Jack was a second at a bare-knuckle fight between Jack Massey (who Jack had defeated in July) and William Middings. The venue was a field in Charshalton, near Epsom. The bout began at 7 a.m. and the two men fought for 70 minutes before 'a posse of police appeared on the scene'. Most of the spectators fled, but the fighters were 'not in a condition to help themselves'. Jack stayed and was helping one of the fighters to dress, when he was arrested. Together with ten others, Jack appeared at the Croydon Borough Police Court in the afternoon, where he was given bail at £50 plus another £50 from his own recognisance. The case was later heard at the Surrey Sessions, and Jack was fined 40s.

Jack said that "I next fought Woolf Bendoff with the gloves, for endurance, and defeated him in three rounds easily." This bout was on 14th October 1884 and Jack won with a knock-out.

Between 1884 and 1886, Jack defeated several 'minor opponents'.

In January 1885, Jack appeared at the Queen's Theatre in Poplar, London, where he 'sparred two or three friendly rounds with Mr Mace, who was received with round after round of applause'. He also appeared at the South London Palace in the evening of 18th February where 'there was plenty of enthusiasm over the appearance behind the footlights of Mr James Mace, the champion boxer, and his companions, Messrs Knifton and J. Kemp, who had been added to the regular company.'

In July 1886, Jack and Jem Moore went on an exhibition tour in Britain. On 23rd September 1886, Jack also had an exhibition match with Jem Mace at Newmarket.

In reporting on Jack's upcoming fight with Jem Smith, a newspaper of August 1886 noted that Jack was 'formerly boxing tutor to some of the Royal Princes'. I was told that Jack trained royalty from overseas.

Jack's Last Fight?

One of Jack's most widely report fights was planned to be with Jem Smith. This was to be a bare-knuckle fight towards the end of 1886. Jack was 'in strict training'. During an interview at the time, he said "I first took long sweats early in the morning, and upon returning to my shed in Britannia-street, Hoxton, was bathed by Jem Smith's nephew. All the time, I conducted my regular business as a cow keeper, and did not indulge in boxing for one month. I subsequently travelled with Ginnett's Circus for a month, in company with Jem Mace, sparring with him twice a day, and walking from town to town with the circus, covering 20 miles a day in company with my little boy." Jack added "My son has been with me throughout my training, and accompanied me from Lincoln to London on a pony." Jack's son Frederick David was 9 years old at this time.

Jack then moved into the Park Hotel, south of Wheathampstead, where he trained on Nomansland Common. His son Frederick, and brother David, also boarded at the hotel.

|

The Park Hotel and Nomansland Common where Jack trained in the late 1880's

Jack's first trainer was Pooley Mace who made Jack run "four miles sweats twice round the Common, varied by punching the sack and using the dumb-bells." However, Pooley became ill and Jack employed John Hicks (also known as 'Jack') as his trainer, who was said to have revolutionised his training routine:

"Up every morning at six o'clock, and at half-past generally on the road, covering four miles before breakfast; then one cup of tea, some steak, chop, or eggs, according to my fancy, and dried toast. Hicks prepares my morning meal. At ten o'clock I put on my sweaters, and run and walk six miles, and sometimes twelve, Hicks being my companion. On arriving at my quarters I am bathed and rubbed on a bed for three-quarters of an hour, then indulge in a rest until dinner. My second meal consists of beef or mutton, with a few vegetables, and half a pint of old ale. This usually occupies two hours, including a brief rest. My next work is a thousand punches at a sack containing straw suspended from the ceiling, occupying thirty minutes. But instead of a sweat on wet days, I have smacked the sack three or four thousand times, and thus encouraged perspiration. Then, after being well holystoned, I would walk five miles out and home—sometimes to Luton. I have mostly finished each day's work with a four miles' walk, and at night amused myself with a game or two at draughts or whist."

Jack also explained that he generally went to bed at 10 p.m., used a skipping rope on very wet days, and with regard to dumb-bells, "I exercise with them before going to bed and as soon as I awake, always keeping them at my bed side." He also "frequently played football with the curate of the parish and other members of the club."

The police discovered where he was training and, according to Jack "the Chief Inspector of Police, with a squad of constables, arrived in a 'bus from the Hitchin Hotel after a night's journey, at 6 a.m. I was up, and seeing them, bolted." Jack Hicks explained "the Inspector and a policeman went into the parlour, whereupon I pulled the door sharply to, and Knifton rushed out. Directly, however, Knifton got far enough away, I entered the room. The Inspector then asked if he could see Knifton. I said 'No. He has gone out for a walk.' After looking very hard at Knifton's brother, he then said, 'Isn't that him?'" Jack ran to the home of Tom Thrailes, the local baker, "who hid me for three hours; but not in the oven".

Jack was a tall man. He tells us in November 1886 that "I was measured the other day, and in my socks was exactly 6ft. 1½in. When I started training I was fully 16st., but now scale in fighting costume 13st. 11lb." This was a significant improvement to the 17st. 4lb. he weighed four years earlier, and Jack is reported to have vowed never to put on weight again.

The fight between Jack Knifton and Jem Smith for the English Championship and £400 was scheduled for 1st December 1886, in France. Jack had arrived in Paris by 30th November. There was supposed to be only a few spectators - Jack had said that "I only desire my brothers and one or two friends to be present" and that there should be "as few as possible on each side". However, it was reported that 'Knifton and his seconds, finding that a considerable "rough" element was present in support of Smith, refused to go on with the fight'.

|

The fight was rearranged for Monday 6th December in Surrey. Jack and three other men were travelling in a broughman (a four-wheeled horse-drawn carriage) and were stopped by the police. Jack told the inspector "We are not going to trouble you today. You might as well have left us alone for an hour or two." The inspector told Jack 'he had heard what he was up to and he had better return to town quietly'. With this threat of arrest, the party returned to London. The police followed until they dispersed. The fight was later planned for Saturday 11th December, in Epping Forest.

In the early hours of Saturday morning, Jack, Jem Smith, and their supporters, travelled together from Fenchurch Street to Cadwell Street, in Shadwell. Here they got into a furniture van which was to take them to Epping Forest. However, before the van could leave, at 6.40 a.m. it was surrounded by the police, and all occupants were arrested. The police ordered the driver to Shadwell Police Station, where Jack and 14 others were charged with 'an attempt to commit a breach of the peace'.

Later that day, Jack Knifton, Jem Smith, and the rest of those in custody, including Jack's trainer John Hicks, appeared before the Magistrate at the Thames Police Court. It was reported that on searching the van, the police 'found a bag containing ropes and stakes. There were 18 pegs, a pair of boots with spikes in them, a live pigeon, wadding, a towel, a sponge, ointment, a bottle containing sherry, and other articles, among which was a chest preserver (laughter)'. The Magistrate 'remanded the prisoners on their own recognisances to appear on Tuesday week'.

The case was heard at the Thames Police Courts in the morning of 21st December. In giving evidence, the Chief Inspector said 'he had no warrant to arrest the prisoners. He found a box in the van containing resin for Knifton to put on his feet when he danced the Highland fling'. Jack responded and said 'that was quite true. He always used it when he danced the Highland fling'.

The man defending Jack said he knew 'Smith and Knifton as quiet, peaceable men, and teachers of boxing'. The defence focused on the fact that a fight had not taken place - in other cases in which the parties had been found guilty, a fight had actually taken place. Another man defending said 'When the police heard of a prize fight it was their duty to obtain a warrant for the apprehension of the offenders...they had no ground whatever for taking the men into custody. Knifton like many other men, was devoted to the noble art of self-defence, and before the defendants could be committed the magistrate must have distinct evidence that a prize fight was going to take place. There was no evidence to show that Knifton and Smith were prepared for a prize fight.'

The Magistrate believed that a prize-fight was going to happen, and that it was not the duty of the police to have waited until it had taken place. However, he said that 'he did not look with such horror on the prize ring as some people did' and that 'prize fighting in its honest sense had been of immense benefit to this country'. He concluded that the case should go no further, and while two defendants were discharged, Jack and the others were 'bound over to keep the peace in one surety of £10 each', and were allowed to leave the court.

Jack was in the peak of fitness, but the events of December 1886 are said to have ended Jack's connection with the ring.

Vestryman, Bailiff, and Landlord

Jack had already been appointed a church warden of his parish by 1886, and in the years that followed, as well as holding several exhibitions, he began new ventures, and busied himself with supporting those in need.

In 1887, Jack and his brother David began a sparring exhibition tour of Britain. In January they appeared at Westgate Street, Cardiff, as part of Tayleure's 'Great American Circus'.

|

Jack appears to have had one last fight on 15th February 1887, when he lost on points to Charles Wall at Islington. This was followed by two exhibition fights, on 16th and 17th February 1887. Although he was reported to have issued a challenge to Sullivan in 1888, Jack did not box again.

On 23rd September 1887, Jack found the body of his brother David in the Regent's Canal at Haggerston, London. 'A large piece of iron was tied to his neck' - David had committed suicide. John attended the Coroner's inquest the following day, during which he said that he and his brother were on the most affectionate terms and that they had been brought up together by their grandmother in Scotland. David's funeral was reported to have been attended by almost 5,000 people.

John continued to appear in theatre in 1887, including an appearance at the Albert Hall.

Jack and Ann's eight child, Augustus Charles Knifton, was born in January 1887, who was followed by William Ernest Knifton in May 1888.

Jack meanwhile continued with exhibitions, appearing with Jack Massey at Warrington, Lancashire, for six nights in January and February 1888, followed by another appearance at the Albert Hall.

|

Jack and Ann's tenth child Alfred was born in April 1890.

While Ann continued with their cow keeping business, Jack worked as an appraiser and broker, a house and estate agent, and also became landlord of housing at 116 Britannia Street, Shoreditch. He continued to be a vestryman, being 'returned at the head of the poll in the Hoxton Ward' in May 1889

On 3rd June 1889, Jack attended an inquest on the body of a four year old boy who had 'been left in charge of a woman named Wells at 116, Britannia Street, Hoxton'. It was reported that 'on the 8th ult. Mrs. Lyons, who lives in the same house, heard screams from the ground floor, and on going down to see what was the matter she saw the deceased tied to a chair lying on the floor. He was crying bitterly, but as the door was locked she was unable to obtain admission. She sent for Mr. John Knifton, the ex-champion pugilist, now a vestryman, who is landlord of the houses. Jack said that 'he was called to the house and found the door locked. He then went into the back yard and looked through the window, and saw the child on his knees with his head down, tied to the rails of two chairs'. He then went to the Police Station, 'and with an officer returned and broke in the door and released the child'. Jack is said to have informed the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, who moved the boy to another address. However, he died a few days later.

Jack is also said to have been a journalist, and 'one of the sheriff's bailiffs'. In November 1889 he was helping a Professor who was investigating the condition of people of the East-end of London. It was reported that 'Mr. Jack Knifton, ex-pugilist, but now a vestryman, house and estate agent, sheriff's bailiff, and journalist, has been accompanying Professor Stuart through some of the more dangerous slums of the East-End. I would not wish for a more satisfactory protector, and congratulate the Professor on his escort. Mr. Knifton is, we are told, a model vestryman, an unsparing exposer of jobbery, and has done much good in connection with the housing-of-the-poor question.'

By 1891, Jack, Ann, and their children, had moved to 175 Burtonville Road in the Pentonville area of Clerkenwell Parish. On the census return he described himself as a 'broker and appraiser', and also an employer. Their eleventh child Annie was born here in June 1891.

An article from 1934 claimed that as a licensed broker and appraiser, Jack had 'premises on Pentonville Hill, where was stored a wonderful collection of such articles as one usually sees in an auction-room owned by a gentleman who clears out by virtue of a warrant to him directed, the ramshackle dwellings of the impecunious'.

|

Jack Knifton's visiting card

Jack and Ann's family continued to grow. In May 1893, their twelfth child Otto Bismark Knifton was born, and by this time, the family had moved again. Jack was the landlord of the London Assurance Public House at 193 & 195 City Road, Shoreditch, which he purchased for £4,000, and where the family were now living. An incident here involving Jack and his son Arthur was reported in several newspapers.

|

In October 1893, entertainment was provided at the Empire Theatre of Varieties, Liverpool, by 'Jack Knifton and Professor Marx, in their boxing bouts and feats of strength'. Jack was essentially appearing as a 'strong man'.

At this time, Jack was also working as a bailiff for the Clerkenwell county court. On 30th October 1893, he appeared at the Clerkenwell court as one of three defendants against a claim of damages for trespass, to health, loss of trade, distraint, and slander. The plaintiff claimed that Jack had forcibly entered his premises. One of the other defendants explained when Jack and himself demanded admission to the premises, the plaintiff 'put his son through a window, and told him to go for the police. Knifton then remarked, "Oh, if that is your way out, then it is my way in". Knifton, when going into the window, was struck on the head repeatedly with an iron bar [by the plaintiff] while the son hung on to his legs'. Judgement was given in favour of the defendants.

Around 1894, Jack was called as Bailiff to the home of the daughter of Reverend Thomas Robert Keppel, formerly of North Creake in Norfolk. The Lady and her husband had ten children and their rent had fallen into arrears. In the past, Jack appears to have received gifts from the Lady's Uncles, so knew the family. As Bailiff, Jack was to sell the house 'but the Bailiff was a man with a faily of his own and a heart that could feel for misfortune... and he put his hand in his pocket and provided the money to settle the debt himself'.

The Lady was expected to receive an income of £450 from her father's Will, but the Trustees of the Will somehow blocked this, which would result in her falling into debt again. In order to help her, Jack decided to seek contributions from people of Norfolk in the form of the 'Keppel Relief Fund'.

|

Jack sought approval of the Fund from other members of the Keppel family, but the Lady's brother, Major Keppel, objected, and ordered a 'Caution' to be issued in the Norfolk Chronicle on 8th August 1894. The caution contained criticism of Jack and of Arthur Blott, secretary of the fund. Jack and Arthur responded to the criticism by writing letters to the newspaper, which were initially published. There then followed a subsequent letter responding to Jack's letter. The newspaper refused to publish further letters from Jack and Arthur, and although Arthur was initially able to use a paid advert to make a response, he had to arrange for a pamphlet to be printed.

Written by Arthur Blott, 'The Keppel Relief Fund and How It's History Came to be Published' pamphlet described the circumstances giving rise to the fund and was critical of the Keppel family of not helping the Lady. The pamphlet reproduced a letter from Jack which was written on 25th September 1894 and printed in the Yarmouth Gazette on 29th September. In the letter he wrote that he was a retired pugilist and the 'Guardian and Vestryman of the parish lived in from boyhood' and that he was the 'Proprietor of the house I live in'. He also wrote that during 'the late Cab Strike I fed from 300 to 400 Cabmen daily, at my own expense'.

Jack explained in the letter that 'As Bailiff, it was my duty to sell the home of Major Keppel's sister, and I saved it by finding the money myself and giving it back to her' and that he opened his 'purse to the extent of about £50'.

The pamphlet reproduced a second letter written by Jack on 19th September 1894 to the Editor of the Norfolk Chronicle, but which the newspaper refused to print. In it he wrote that since retirement "I have interested myself much in charity, in many instances in conjunction with Lady Frances Jeune, Lady Colin Campbell, Miss Douglas and Miss Barry, Princess Christian and the Marchioness of Tweeddale, Earl Compton, and many others of the nobility". In addition, 'During the last three years I have joined with others, viz., The East Finsbury Radical Club, in feeding 300 children a week'. He goes on to state that 'I am John Knifton, Proprietor of the 'London Assurance,' City road, E.C. I gave £4,000 for my house'. Next to his name he recorded 'Certified Bailiff'.

I do not know how the 'caution' was resolved, or if the 'Keppel Relief Fund' was a success. The pamphlet by Arthur Blott can be read here. Jack stated that he would prepare a similar pamphlet but it is not known if this survives.

In the evening of Friday, 18th January 1895, Jack was the 'recipient of a supper given by a number of his progressionist brother vestrymen of Shoreditch and St. Luke's to celebrate Jack's return to that hard working parochial body'. The supper was held in the Drawing Room at Jack's pub, the London Assurance, on City Road. The event lasted 'until the small hours of the morning, when everyone went home, after having thoroughly enjoyed themselves'.

In April 1895, John attended the Amateur Boxing Championships at St. James' Hall, London, with two of his sons. He was a visitor, rather than a competitor.

In November 1895 Jack appeared in a melodrama at the Princess' Theatre called 'The Dark Secret'. The play used 200 tons of water 'in the vivid realisation of the Henley Regatta and Marlow Lock scenes'. The Penny Illustrated Paper reported that 'Mr. Jack Knifton infuses pugilistic importance to the part of the prize-fighter. "A Dark Secret" is the most wonderful water-drama London has seen'. Demolished in 1931, the Princess' Theatre was at 73 Oxford Street, London.

Jack continued to be involved in boxing, although by now he was only providing stake money. He was involved in a court case in 1896 to recover £200 in stake money, although the defendant settled before the case went to trial.

In March 1896 Jack and Ann's thirteenth child, Gwendoline, was born. She was to be their last child. In the same month, Jack became ill, and was instructed to rest in bed, although by April he was reported to be recovering.

|

Over the next month Jack's health continued to deteriorate.

|

John ('Jack') Knifton died at 1.40pm on 6th May 1896 at his home, the London Assurance. He was 41 years old. His death was attributed to nephritis, then known as Bright's disease, and 'an expanded liver'.

The news of Jack's death was widely reported across England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and Australia.

|

Jack was buried at Abney Park Cemetery on 12th May. He was interred in the same grave as his parents and brother David.

|

The forgotten headstone which includes an inscription for Jack Knifton

|

Jack was a man of his word. One day when out fox hunting, he was introduced to the Chief Constable of Hertfordshire. Jack said that "I explained to him, and gave him my word of honour that I would not fight in his county, intimating that he might save himself anxiety, and his men the trouble of watching me. I am proud to say he took my word, and withdrew the police immediately. Now, no amount of money would induce me to break my promise."

Of his fights, he said "all I want is fair play, and the best man to win. I don't care where I go to, or how far, so long as I have a fair deal."

A comment by Paul Pry, who interviewed Jack in 1886, reflects how well Jack was liked:

'As the 81-Tonner stood towering above me, smartly dressed, with the ruddy glow of health...I thought him physically one of the finest specimens of humanity I had ever seen. His simple, winning way was distinctly noticeable, and I must confess that I caught the infection with which Knifton, figuratively speaking, has inoculated the entire district, from parson to ploughman, all of whom speak in the highest terms of the pugilist.'

|

Jack Knifton, October 1893

Jack didn't leave a Will, and administration for his effects was granted to his widow Ann in London on 5th June 1896. Valued at £10, Jack appears to have arranged his affairs to minimise death duties. Jack treasured an 1847 bound edition of 'Sporting Life' which he believed was the only one in existence. It is not known if Jack had any boxing trophy's. His family still keeps a poster used when he went on tour in East Anglia. Two pewter mugs, one engraved with his initials and the other with Ann's, still exist, as do a set of pewter measures which were used in his pub.

Ann's later Life

After her husband's death, Ann sold the London Assurance pub in January 1897 and moved to 87 Listria Park in Stoke Newington, London. Six months after Jack's death, their daughter Gwendoline died on 8th November and was buried at Abney Park cemetery. She was 9 months old.

At the time of the 1901 census, Ann was living at 87 Listria Park with her married son Frederick and his wife, her sons Benjamin, Augustus, William, and Alfred, and her daughter Annie. The house had six rooms, including the kitchen, with a bedroom also on the first floor to the front. By 1911 Frederick and Augustus were each paying rent of five shillings a week to their mother.

Between 1911 and 1918, Ann moved to 8 Greenleaf Road in Walthamstow, London, where she continued to live until her death on 19th September 1933. She was 80 years old.

|

Ann was buried at Abney Park Cemetery on 23rd September. Although interred in the same area as her husband Jack, she was not buried in the same grave, since it was already full.

Administration for Ann's effects was granted to her daughter Annie and son William on 4th November 1933, valued at £829 19s. 8d.

Jack and Ann Knifton have many descendants in England and the United States.